Why India’s political start-ups rarely succeed

2025-11-15 02:55:39

Sutek BiswasIndia Correspondent

Hindustan Times via Getty Images

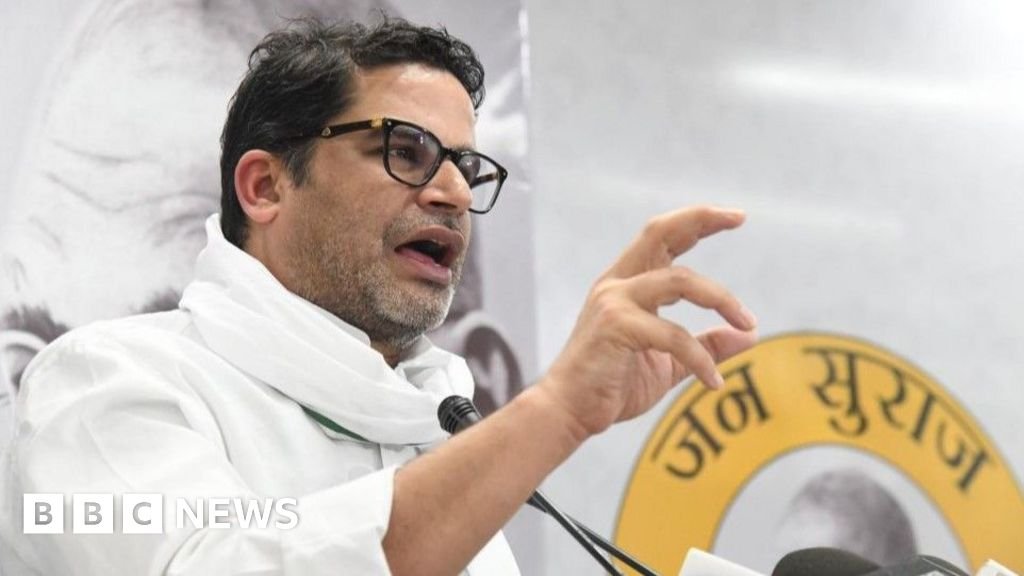

Hindustan Times via Getty ImagesFor more than a decade, Prashant Kishor has been India’s magician behind the scenes — a political strategist trusted by everyone from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to powerful regional leaders like Nitish Kumar and Mamata Banerjee.

But when the 48-year-old entered the arena himself, the spell wore off.

Kishor launched Jan Suraj (Good Governance for the People) with the swagger of a data-driven political start-up and the promise of breaking the cycle of recession in Bihar, India’s poorest state.

He spent two years crisscrossing the state, building an ingenious organization and fielding candidates for nearly all 243 seats. The media hype was huge, but Jan Suraj failed to win a single seat, receiving only a small portion of the votes. Modi’s coalition led by the Bharatiya Janata Party came to power.

For all the attention Kishor received – often more than the founding leaders – the party was unable to convert its appearances into votes. In India’s overheated political market and deep divisions, many believe his debut represents a cautionary tale: the system is much more difficult to penetrate than it is to diagnose its faults from the outside.

The recent history of Indian politics confirms this.

Since the emergence of the regional Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in 1983, very few new parties have crossed the threshold of importance. Those parties that participated in the elections – from the Trinamool Congress in West Bengal to the Biju Janata Dal in Odisha – were splinter factions of the main parties, based on existing social bases.

Others, such as the Asom Gana Parishad in Assam in 1985, or the Aam Aadmi Party in Delhi decades later, rode on the back of mass mobilizations and political crises. Kishore’s Jan Suraj was having neither. It was not born from a movement in the street, nor did it turn into a moment of anger against the incumbents. Despite its many problems, Bihar in 2025 seemed largely content with the status quo.

“There was no anti-incumbency wave, as voters stuck largely to entrenched political and social loyalties,” says Rahul Verma, a political science professor. “Without a clear crisis or widespread discontent, Kishor’s party never emerged as a credible alternative, despite hard work and mobilization.”

Jan Suraj’s debut in Bihar also contrasts sharply with most new Indian parties.

While parties like the AGP, TDP and AAP arose from “socio-political movements that already had deep emotional and popular resonance,” and the AAP was born from a mass anti-corruption movement, Jan Suraj was conceived as an “intellectual and strategic project” — a strategy-driven initiative to fill what Kishore called a “political vacuum,” says Saurabh Raj of the Indian School of Democracy in Delhi.

AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images)“The subsequent padayatra [a long, grassroots walk across the state to meet people] Try to turn that intellectual idea into a grassroots campaign. But it still lacks the organic, movement-based energy that usually propels new parties to their place. In this sense, Jan Suraj looks more like a ‘designed political debut’ than a party born of agitation or unrest,” adds Raj.

Kishore is betting that this carefully crafted political project can replace a loyal electoral base.

He spoke of governance, jobs and forced migration for jobs and education, a compelling agenda in a country long besieged by sectarian and patronage politics. Reaching out to Bihar’s 130 million, mostly young, population, Kishor brought hype, style, charisma — even memes.

But many believed his party lacked the combustible emotional energy that drives insurgent political groups. Kishore’s refusal to contest a seat himself may have deepened doubts about whether he is experimenting or offering an alternative.

The Bihar ruling revealed a structural truth of Indian politics: attention does not equal regulation, and hype in the absence of ground power can backfire.

As Raj points out, Jan Suraj “failed to become a serious contender for any seat”, and even his modest vote share “shows the gap between vision and power”. He says the party enjoys recognition, but it has no natural social base – no class, religion, gender or urban constituencies like its rivals.

Verma puts it more bluntly: Startups fail more often than they succeed—in business and in politics.

He adds: “We tend to remember only successes, but most new parties fail.”

Verma says building a party requires vision, organization, mobilization and the right candidates, each of which presents a separate challenge, especially given the lack of a track record of voter trust. Jan Suraj has fielded candidates for all 243 seats, most of them first-time candidates.

So what does the failure of Jan Suraj, Kishore’s leading figure, tell us about Indian voters? Kishor attracted crowds wherever he campaigned and was visible and dominant in media coverage – yet his party lost to a coalition led by 74-year-old veteran Nitish Kumar, who was betting he would never return to power.

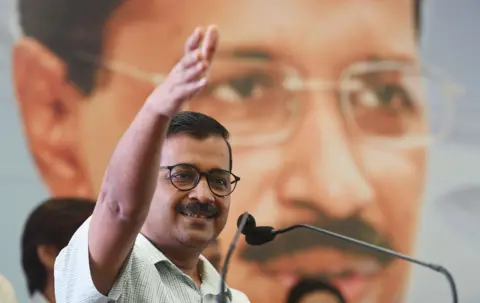

Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

Hindustan Times via Getty Images)“Indian voters today are more politically aware and issue-sensitive than ever before, but they also remain very realistic,” says Raj. “They often appreciate the novelty of a new agenda but tend to ‘vote safe’ unless they are convinced of the viability of the party.”

He believes Jean Suraj’s focus on governance, jobs and immigration was coherent and attractive, but without a charismatic electoral face, voters struggled to see that as a winning alternative.

By contrast, the association’s early success in Delhi hinged on anti-corruption activist Arvind Kejriwal running personally against Sheila Dikshit, the then chief minister of Delhi, a symbolic act that turned volunteers into voters.

“Kishore’s decision to step away from the competition limited that emotional connection and credibility,” says Raj. “For new parties, a compelling agenda is important, but a relatable, risk-taking leader who embodies that agenda is often the turning point.”

However, this may not be the end for Kishore’s party. In the past, he promised to stay in Bihar and strengthen its popular presence and agenda if he lost the elections.

Raj believes that if Jan Suraj can maintain a steady presence on the ground, grow local leadership and avoid the “post-election dormancy” that traps many new parties, he may gradually turn attention into influence.

“The political landscape in Bihar is volatile, traditional caste loyalties are evolving, and there is a growing appetite for credible alternatives,” he says. “If Kishor chooses to lead from the front politically rather than strategically, and continues popular engagement beyond the election cycle, Jan Suraj could become a meaningful electoral force by 2030.”

As one local voter told a reporter in a village in Bihar: “People might respond to that [Kishor] In the next elections. “This time, he’s just getting his feet wet. He’s not a superhero who can fly right away.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/5df4/live/111bf9f0-bfb4-11f0-8669-5560f5c90fbe.jpg

إرسال التعليق