The Indian cartoonist who fought the censors with a smile

2025-07-07 20:46:06

BBC

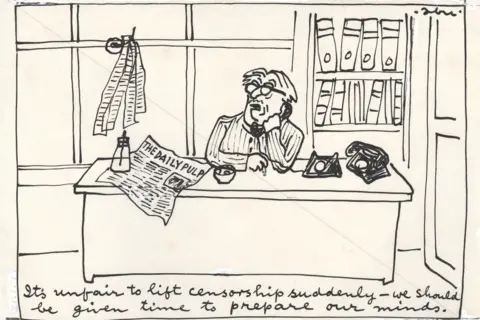

BBC“It suddenly raises the censorship,” the editor of a distorted newspaper, which is a copy of the daily pulp, dies through his office. “We must give time to prepare our minds.”

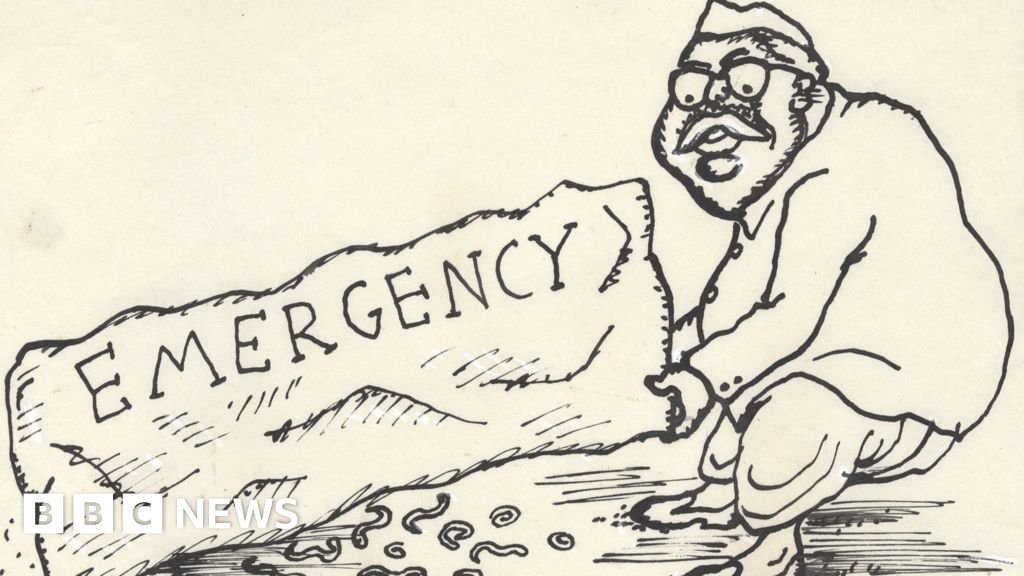

The cartoon that picks up this moment – the hole and satirical – is the work of Abu Abraham, one of the best political cartoonists in India. His deviant pen on elegance and edge, especially during 1975 Emergency21 months of suspended civil freedoms and popular media under the rule of Indira Gandhi.

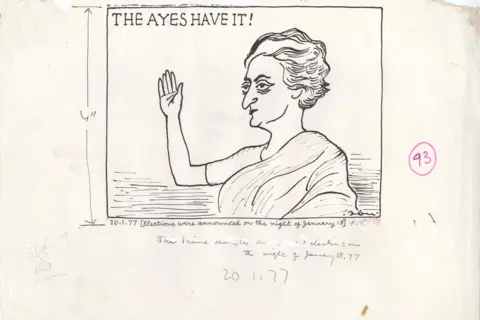

The press was left overnight on June 25. The Delhi newspaper presses the lost authority, and morning censorship was law. The government asked the press clause to its will – and as opposition leader LK Advani noticed later, many noticed “chose to crawl.”

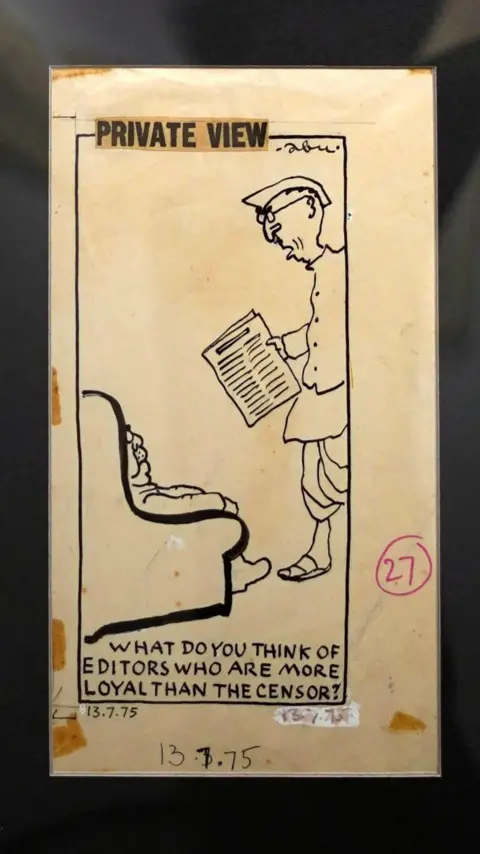

Another famous cartoon – Abu signed them, after the name of the pen – from that time a man appears asking another: “What do you think of the editors who are more loyal to censorship?”

In many ways, after half a century, the animation is still in Abu Sahih.

India is currently classified 151 In the International Press Freedom IndexIt was collected annually by the reporters without limits. This reflects Increased fears About the independence of the media during the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Critics claim to increase pressure and attacks on journalists, high -end media and a shrinkage space for opposition voices. The government rejects these allegations, and insisted that the media remain free and vital.

After nearly 15 years, he drew caricatures in London for the observer and Guardian, Abu returned to India in the late 1960s. Join Indian Express as a political cartoonist at a time when the country was wrestling with severe political turmoil.

He later wrote that the pre -installation – which requires newspapers and magazines to submit their news, editing and even advertisements for government control before publishing – began two days after the emergency announcement, a few weeks later, then it was re -imposed after a year for a short period.

“As for the rest of the time, I had no official intervention. I did not disturb myself by investigating the reason for allowing me to continue freely. I am not interested in discovering.”

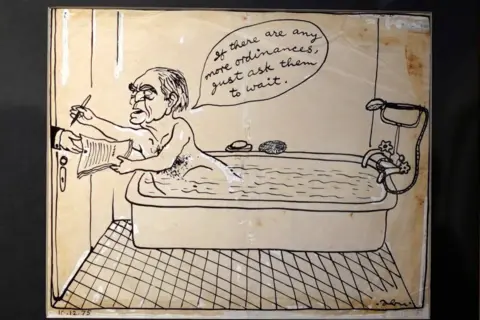

Many cartoon fees for the emergency era in Abu Makha’a. One of them appears at the time, President Fakhudin, Ali Ahmed, signs the advertisement from his bathtub, where he acquired the wheel and laugh that was issued (Ahmed declared the emergency that Gandhi issued it shortly before midnight on June 25).

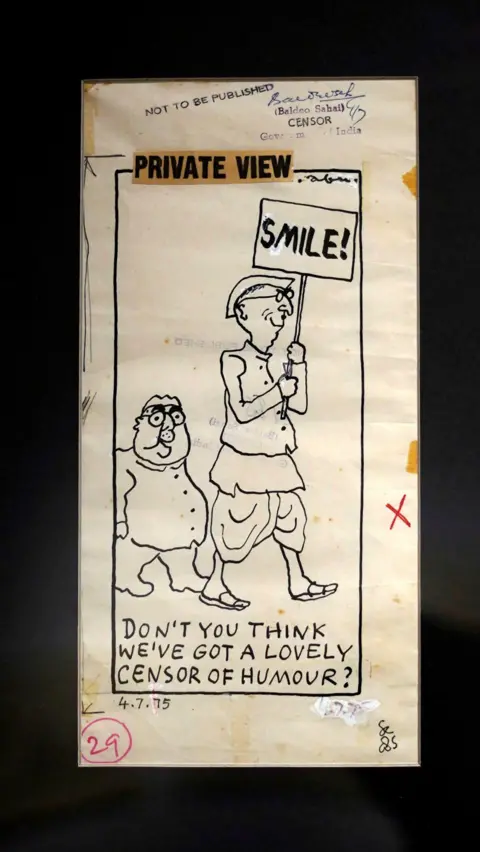

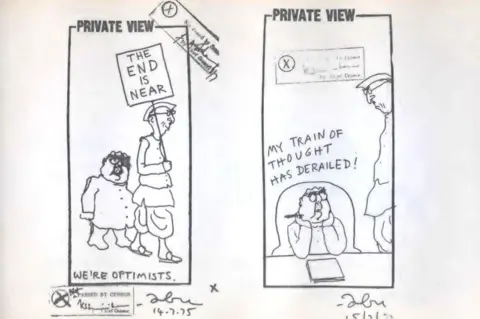

Among the amazing ABU works, there are many caricatures sealed boldly with “not going through censorship”, a flagrant sign of formal repression.

In one, a man holds a sign that reads “a smile!” – A malicious blow in the government’s lobby campaigns during the emergency. His companion Deadpans, “Don’t you think we have a beautiful observation of humor?” A line that reduces the heart of the chanting that the state pays.

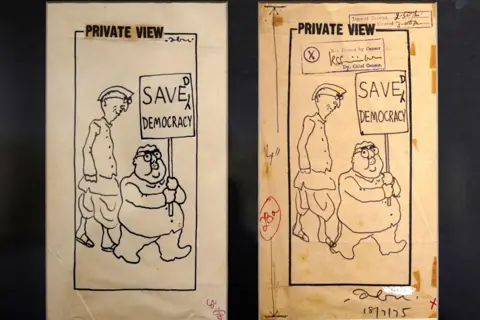

Another non -harmful caricature appears to be a man in his office sighing, “My thinking train has come out.” Another protesters bearing a mark reading “preserved democracy” – “D” was added embarrassed at the top, as if democracy itself was a late idea.

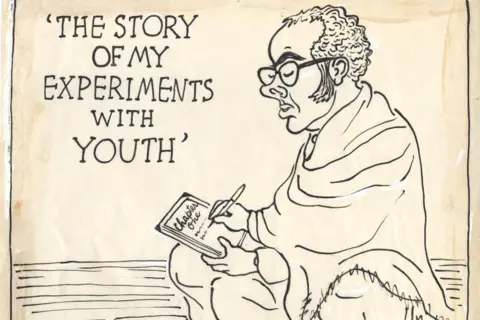

Abu also assumed the goal of Sanjay Gandhi, the non -elected son of Andra Gandhi, who many believed to have conducted a government during the state of emergency, and they had power without deterrence behind the scenes. Sanjay’s effect was controversial and feared. He died in a plane crash in 1980 – four years before the assassination of his mother, Indira, by her personal guards.

Abu’s work was intensively. “I have reached the conclusion that there is nothing but political in the world. Politics is simply anything controversial and everything in the world is controversial,” he wrote in Nadawi magazine in 1976.

He also launched a state of humor – tense and manufactured – when the press was honored.

“If it is possible to manufacture cheap humor in a factory, the audience will rush into lines in national shares stores throughout the day. When our newspapers become boring, the reader, drown in boredom, clutches in each joke. [India’s state-run radio station] The news bulletin at the present time looks an annual title for the company president. The profits are carefully and detailed, the losses are deleted or low. Abu Al -Saejin wrote reassuring.

In the tongue column in the cheek in The Sunday Standard in 1977, Abu mocked the culture of political compliment through a fictional narration of the meeting of the “All India Sycophantic Society”.

The sarcastic simulation of the association’s fictional president declared: “The real non -political sycophance”.

The satirical monologue continued with fake ads: “Sycophance has a long and historical tradition in our country …” Grapes before Self “is our slogan.”

Abu vision of the guidance association was crowned: “Touching all available feet and promoting a wide compliment program.”

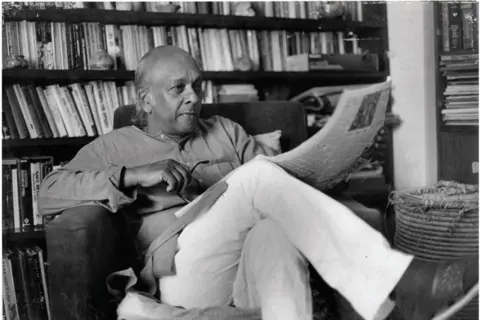

Abu was born in the role of AttuPurate Mathew Abraham in the southern state of Kerala in 1924, and began his career as a reporter in The National Bombay Chronicle, driven by the bid of its charm with the power of the printed word.

His years coincided with India’s dramatic trip to independence, and witnessed the euphoria that acquired Bombay (now Mumbai). He later indicated that “the press has excuses being a crusade, but it is often an incentive for the current situation.”

Two years later with Shankar’s Weekly, a well -known satire magazine, Abu put his attention in Europe. She presented an opportunity to meet with British cartoonist Farid Jose in 1953 to London, where he quickly made a mark.

The cartoons were first accepted by the Punk within a week of arrival, and he got praise from the editor Malcolm Muggeridge as a “magician”.

ABU, the political company, started a two -year competitive scene in the competitive scene in London, and soon attracted the attention of the observer editor David Astor.

Astor presented to him the position of the employees with the paper.

“You are not cruel like other cartoonists, and your work is the type I was looking for,” he told Abu.

In 1956, based on the proposal of Ator, Ibrahim adopted the name of the pen “Abu”, and the writing later:

Astor also assured him of creative freedom: “You will never be asked to draw political animation that expresses ideas that do not personally sympathize with.”

Abu worked in the observer for 10 years, followed by three years in the Guardian, before returning to India in the late 1960s. He later wrote that he was “bored” of British policy.

After the cartoon, Abu as a candidate member in the House of Representatives in India from 1972 to 1978. He returned to Kerala in 1988 and continued to withdraw and write until his death in 2002.

But Abu’s legacy was never about the punching line – it was about the deepest facts that his humor revealed.

He also noticed once, “If anyone notice a decrease in laughter, the reason may not be the fear of laughing at power, but the feeling that reality, continuity, tragedy and comedy have been mixed in one way or another.”

The lack of clarity of absurdity and the truth often gave his work on the edge.

He wrote during the state of emergency: “The year of the year of the year of the year must go, as he must go to the correspondent of the Indian News Agency in London, who was quoted as a British newspaper’s comment on India under the emergency, that” the trains are working on time ” – we do not realize that this is the usual English joke about Italy in Mussolini.

Caricature and photography of Abu, courtesy Ayisha and Janaki Abraham

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/cc5b/live/8255f240-5274-11f0-a2ff-17a82c2e8bc4.jpg

إرسال التعليق