The ‘bogan’ Australian giving War & Peace an irreverent remake

2025-11-14 22:00:42

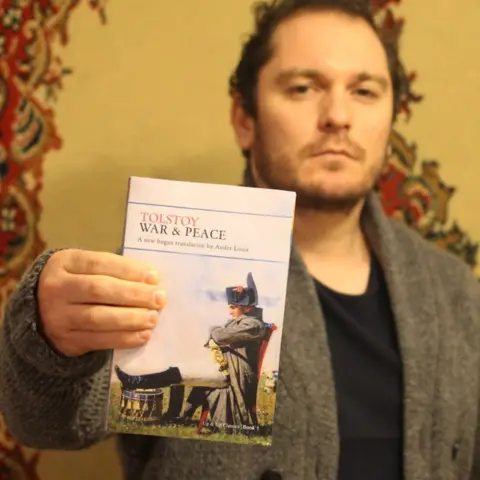

Ander Lewis

Ander Lewis“At that moment, Prince Andrei walked up to Anna’s joint. He was the husband of the pregnant Sheila. Like his lady, he was very good-looking.”

These lines are straight from a new translation of Leo Tolstoy’s epic novel War and Peace, set in the world of Russian high society in the early 19th century.

Except this is the “Bogan” version translated by Ander Lewis, the pseudonym of a Melbourne IT worker who doubles as a writer.

He poured a metaphorical Australian beer can onto the novel by transforming Tolstoy’s prose into language that wouldn’t seem out of place in the popular Australian sitcom Kath & Kim.

Lewis, whose real name is Andrew Tesorero, told the BBC: “That’s how you tell things in a bar.”

The 39-year-old started the project in 2018 as a joke, turning Russian princesses into ‘Sheila’ and princes into ‘Drongo’, but is now on the verge of signing a book deal.

“The first reason I did it was to make me laugh, and I thought if this makes me laugh, maybe other people will too, so let’s get it out to the world.”

Bogan, a term that first appeared in Australia in the 1980s, initially meant “an unsophisticated, uncultured person” with negative connotations, but not for Lewis.

Getty Images

Getty Images“I never thought of it as an insult, or just a term of endearment,” he says.

And his version of the Russian literary masterpiece – which begins with the words “Bloody Hell” – is all about being rude and disrespectful.

“It’s just a good exclamation point to the surprise,” Lewis joked.

Elsewhere, the noble is a fair dinkum, while the death of an important character is announced by the phrase “It’s a cactus.”

“It changes the tone noticeably,” Lewis laughs.

Accidental expert Tolstoy

For years, Lewis avoided tackling War and Peace, set during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century, because of its weight.

The novel is divided into 15 books plus an epilogue divided into two parts. With over 1,200 pages to browse, it is often viewed as the Everest of literature with prose as insurmountable as the famous summit.

But in 2016, Lewis joined an online community where participants pledge to finish the book within a year by reading at least one chapter — there are 361 — every day.

He loved it so much, he did it twice.

“I became an expert by accident,” he told the BBC from Lilydale, on the outskirts of Melbourne.

During this time, the freelance author was writing a novel with dark psychological themes, and in order to lighten the mood, he began making War and Peace irreverent and funny.

For more than six years, Lewis’s project remained a little-known leisure hobby, self-publishing the first two translated books of War and Peace and selling a small number of copies.

That all changed earlier this year when a New York-based tech writer found the fake copy, publishing excerpts from Louis’s book in which he described Napoleon as a “good guy,” the high-ranking Prince Vasily as a “very big deal” and Princess Bolkonskaya as a “smoking hottie.”

“Suddenly, it went viral. Overnight, I sold 50 copies,” Lewis says.

The father-of-two believes US interest in his mock translation may be due to the “Bluey Effect” given the popular Australian children’s cartoon has been the most-streamed show in the US for almost two years.

“Australian ideas are popular there at the moment.”

How Bogan became its own language

At first glance, Tolstoy’s book, filled with the lives of rich and powerful Russians, seems quite removed from contemporary Australia.

But Lewis sees bogan as the ultimate equivalent because the informal slang applies across the social spectrum, whether in Australia or the world of Russian aristocrats.

“There are a lot of different types of bogan,” Lewis says.

Mark Gwynn, a senior researcher at the Australian National University who helps compile the Australian National Dictionary, agrees. “Bogans can be rich, poor or middle class, so it’s more about the way they act, dress, socialize and talk,” he says.

He says that more recently, the term has also been used affectionately for someone who is considered an animal or even to refer to oneself like the term “inner animal.”

He says that speaking “bogan” refers to informal speech that contains many local sayings.

“Most Australians will know if you say ‘Bogan speaking’ or ‘Australian Bogan’ that the language will be highly informal with many colloquial and colloquial words and phrases, including uniquely Australian words.”

But there is no direct translation of this term in correct English – it is uniquely Australian.

“Bogans can live in it [both] “Rural and urban, so it doesn’t equal hillbillies, pumkins, yokels, and country folk,” says Gwen.

Heathens are also not like rednecks, in that they can hold diverse political views, while the British term “chav” – usually used in a derogatory way to describe people from a poor background – does not apply either.

Those shifting, imaginative qualities combined with Lewis’ diverse resume—kitchen worker, energy analyst, Uber driver, rock singer, and Tokyo resident—make him “strangely qualified” to create a bogan translation.

“When I paint on sounds, it’s completely inspired by things I’ve seen and done… through all different walks of life.”

Characters in his bogan version say “happy”, friends are “comrades” and those with questionable morals are considered “reckless”.

The beautiful ladies are “elegant girls”, one of whom is so glamorous that she is “as sexy as a tin roof in Alice” – a reference to the sweltering heat of Alice Springs’ desert landscape.

One of the princes is an “absolute true blue legend” and his vibrant eyes “burn like a forest fire” while the other is “a bit of a Yubo” who believes the others are “carrying on like a bunch of goons”.

While his version is full of profanity – which the BBC cannot publish – part of the appeal is to make the book more accessible.

“The best feedback I’ve found is that people say it’s easier to understand what’s going on,” he says.

Louis likens himself to Pierre, the main protagonist of War and Peace, who represents the “everyman” as the illegitimate son of a wealthy aristocrat who inherits a huge fortune, thrusting him into Russian high society.

He says he feels like the “bumbling clown” in the “walled garden that is traditional publishing” and that he has committed a kind of “plagiarism.”

“I leaned over the fence… and just pinched off the crown jewel – their most revered book – and took it down the pub.”

What does Tolstoy – who, although born a nobleman, later in life renounced his privileged upbringing and wealth – think of the pagan version?

“I actually think he’ll get a kick,” Lewis says.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/397b/live/29b928b0-c145-11f0-8456-eff94716b162.jpg

إرسال التعليق