Pakistan’s army chief gets more powers and lifelong immunity

2025-11-14 23:49:17

Carolyn DaviesPakistan correspondent in Islamabad

Environmental Protection Agency

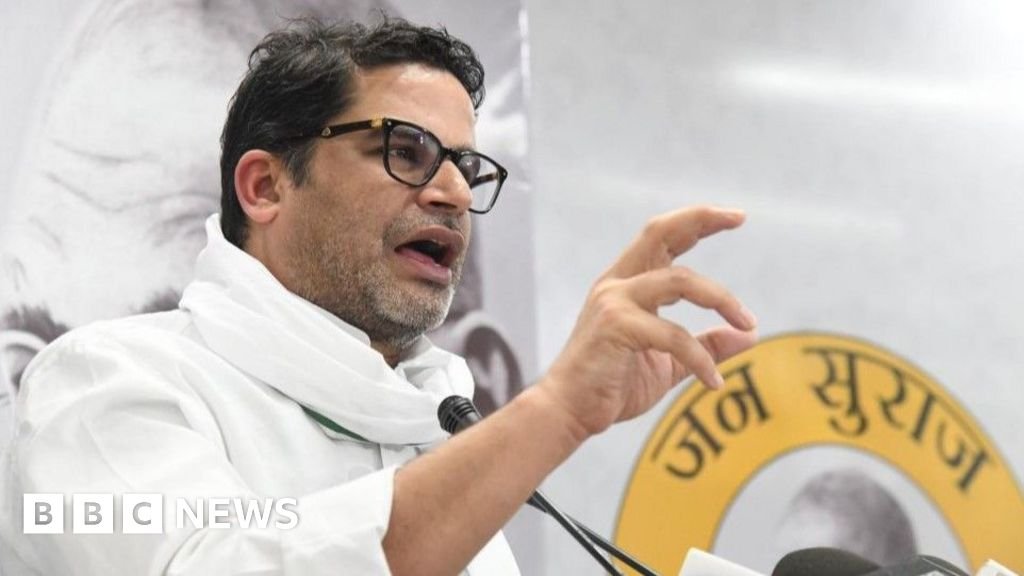

Environmental Protection AgencyPakistan’s parliament has voted to give army chief Field Marshal Asim Munir new powers and lifelong immunity from arrest and prosecution, a move critics say paves the way toward authoritarianism.

The 27th Constitutional Amendment, which was signed into law on Thursday, will also make significant changes to the way the country’s highest courts operate.

Advocates of the changes say they provide clarity and administrative structure to the armed forces, while helping to ease backlogs in the courts.

Pakistan’s military has long played a prominent role in the politics of the nuclear-armed state, sometimes seizing power in coups and, on other occasions, pulling the levers behind the scenes.

Throughout its history, Pakistan has oscillated from more civilian autonomy to overt control under military leaders such as General Pervez Musharraf and General Zia ul-Haq. Analysts refer to the balance between civilians and military as hybrid governance.

Some see the amendment as a sign that the balance has shifted in favor of the military establishment.

“For me, this adjustment is the latest, and perhaps the strongest indicator yet, that Pakistan is now witnessing not a hybrid order, but a post-hybrid order,” says Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute of the Wilson Center in Washington.

“We are essentially looking at a situation where the civil-military imbalance is as unbalanced as possible.”

The latest reshuffle means that Munir, who has been serving as army chief since November 2022, will now also oversee Pakistan’s naval and air forces.

The title of Field Marshal and the military uniform remain for life and he will be given “responsibilities and duties” even after retirement determined by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister.

This is expected to give him a prominent role in public life throughout his life.

Supporters of the bill say it clarifies Pakistan’s military command structure.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif was quoted by Pakistan’s government-run news agency, the Associated Press of Pakistan, as saying that the changes were part of a broader reform agenda to ensure Pakistan’s defense keeps pace with the demands of modern warfare.

But others see it as ceding power to the army.

“There is no balance between the military and civilians,” says Munizi Jahangir, a journalist and co-chair of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.

“They once again directed this power dynamic toward the military and empowered the military at a time when the military needed to be reined in.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is no “separate work space”

The second controversial area of change is the courts and judiciary.

Under the amendment, a new Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) will be established that will determine constitutional matters. The FCC’s first Chief Justice and the justices who serve on it will be appointed by the president.

“It forever changes the shape and nature of the right to a fair trial,” says Ms. Jahangir.

“The influence of the executive has increased not only in appointing judges but also in constitutional bodies. When the state dictates the constitution of those bodies, what hope do I have as a litigant of getting a fair trial?”

Journalist and commentator Arifa Nour says: “The judiciary is now completely subordinate to the executive authority.

“The general consensus seems to be that the judiciary will now have no independent space to operate at the present time.”

Before this amendment was passed, the Supreme Court heard and decided constitutional cases. Some said this led to a backlog of criminal and civil cases waiting to be heard, as judges had to hear constitutional arguments as well, arguing that separating the two helped streamline court proceedings.

This has received some attention from some lawyers, although Salahuddin Ahmed, a Supreme Court lawyer based in Karachi, finds this argument disingenuous. He points out that the majority of cases pending in Pakistan are not before the Supreme Court.

“Statistically, if you were really concerned about accelerating litigation, you would focus on reforms in those cases.”

In the hours after the amendment was signed into law, two Supreme Court justices resigned.

Judge Athar Minallah said in his resignation letter that “the constitution that I swore to preserve and defend no longer exists.”

Justice Mansoor Ali Shah said that the judiciary had come under government control and that the 27th Amendment had “torn the Supreme Court apart.”

Defense Minister Khawaja Asif said of the resignations, “Their conscience has been awakened because their monopoly of the Supreme Court has been curbed and Parliament has tried to prove the supremacy of the Constitution.”

Judges can now also be transferred to different courts without their consent. If they do not agree to the transfer, the judges can appeal to the Judicial Committee and if the reasons for non-transfer are found to be invalid, the judge will have to retire.

Supporters say this will ensure courts in all regions of the country can be staffed, but some worry it will be used as a threat.

“Picking a judge from the district they were working in and moving him to a different high court is something that would put them under more pressure to toe the government line,” says Mr Ahmed. He is concerned that the change will upset the balance in Pakistan.

“[Our judiciary] They have cooperated with dictators in the past, but they have sometimes pushed back on the executive. “I think if you completely take away that hope from people, it will send them in other, much uglier directions.”

Kugelman agrees: “Repressed grievances do not bode well for social stability.”

“It indicates a slide towards authoritarianism,” Noor says, adding that she sees the latest amendment as building on the 26th Amendment, made last year, which gave lawmakers the power to choose Pakistan’s highest judge. There is already speculation about the 28th.

“It indicates that the balance of power is tilted heavily in favor of the establishment.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/c1b3/live/af549250-c138-11f0-8717-7b6a6b2fefad.jpg

إرسال التعليق