Inside one battle-scarred Gaza building, displaced families tell the story of war

2025-10-08 12:15:20

Lucy WilliamsonMiddle East correspondent in Jerusalem

BBC

BBCThe Al-Sikaik building, located on a quiet road off Omar Al-Mukhtar Street west of Gaza City, was a familiar sight for Gaza fans.

The tree-lined street alongside was a favorite courting spot for couples eager to avoid Gaza’s socially conservative outlook.

But the road nicknamed “Lovers’ Street” – and the six-storey building overlooking it – are now surrounded by rubble. There are only a few residents left who remember the good old days. Those who are hiding here now are not fleeing from Gaza’s taunts, but from Israeli tanks.

The war in Gaza has left this once-radiant neighborhood in ruins. The elegant shops and restaurants that line the beach are now littered with shrapnel and bullet holes, and the park, with its French-manicured trees, is buried in gray rubble.

The Sakik building still stands, but its walls are now littered with shrapnel, and a large, cannon-sized hole has been created in the upper floor. Pre-war faces have been replaced by ever-changing confetti of displaced people.

Two years after the start of the war in Gaza, this building offers a snapshot of how the conflict has eroded ties to home and community among Gazans, and what impact this has had.

The previous tenants of the Skeik Building are long gone. Above the closed warehouses on the ground floor, eight of the building’s 10 apartments have become temporary homes for families displaced by the war.

Hadeel Daaban – fourth floor

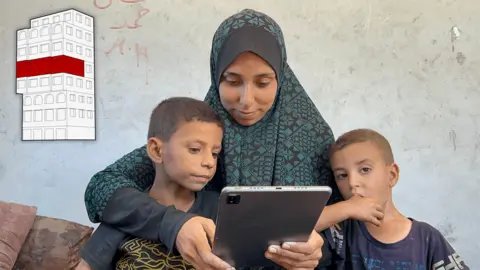

Twenty-six-year-old Hadeel Daban lives on the fourth floor with her husband and three young children: nine-year-old Judy, six-year-old Murad, and two-year-old Mohammed.

The family arrived here two months ago, paying 1,000 shekels ($305; £227) a month to camp in empty rooms.

“The people who were here before us left because the situation was dangerous,” Hadeel said. “Shrapnel hits the walls here, but it’s still better than the tent.”

The family’s few possessions are carefully hidden in piles of bags along the walls. Torn sheets cover the large holes where the windows used to be. It is the twelfth place the family has moved to.

“When loading our luggage onto a cart, I put my children on top of it and ask them to play with things, like kitchen utensils,” Hadeel told me. “I tell them we’re going to live a different life, a little far from the one we lived.”

The family home is located less than a mile away, in the Al-Tuffah neighborhood of Gaza City. They fled in the first week of the war, after a relative’s apartment above theirs was bombed.

They returned a few months later. But on March 15, 2024, an air strike on the building next to them killed Hadeel’s mother-in-law, injured the three children, and buried Hadeel’s husband alive.

She said: “We spent hours searching for him, and we found him under the rubble.”

Her husband, Ezz El-Din, was unconscious. They took him to Al-Shifa Hospital, where Hadeel says her husband suffered a fractured skull and was in a coma.

Three days later, he was still receiving treatment when Israel closed the hospital and began a two-week military operation there to eliminate Hamas leadership positions.

It was only when Israeli forces finally withdrew that Hadil was reunited with her frail but alive husband.

Hadeel told us that he still needs regular medical check-ups. “I was taking him to a neurologist [in Gaza City]But six weeks ago all the doctors moved south.”

Home is not just a shelter or possessions. All three families we spoke to in the Skaik building have moved several times.

“None of my neighbors are my neighbors anymore, because new people come every month,” Hadeel said. “I don’t even know where my original neighbors are – some of them went south, some of them were killed or injured. There are no more neighbors.”

On the day we met our colleague Hadeel, Gaza City was once again empty with hundreds of thousands of people heading to safer areas south.

The Israeli army, advancing through the city, had issued a “final ultimatum” to leave. But the families we spoke to were planning to stay put.

While Hadeel was talking to our photographer, a series of explosions echoed throughout the apartment.

Through the windows, huge gray clouds rose in the middle distance.

None of her young sons backed down.

The “Al-Sakik” building was built in 2008, against the backdrop of the urban boom that swept Gaza City in the mid-1990s. Prime location next to the American International School and one block from the Palestinian Parliament – both now in ruins.

It was this central location, off the main Omar Al-Mukhtar Street, that placed the Skaik building in the path of Israeli tanks during the first months of the war.

Al-Shifa Hospital is located two blocks to the north. Within weeks of the invasion, the Israeli army moved to take control of the complex, saying it was being used as a Hamas base.

The forces approached from several directions, including the roads surrounding Omar Al-Mukhtar Street.

Near the back of the Skaik building, a large rectangular hole had been cut into the wall. Inside, graffiti reads “The Last Samurai” in Hebrew — a reference to the Hollywood film about a 19th-century Japanese warrior outmatched by modern weapons.

We asked the Israeli army whether its forces used the building or fought there. We did not receive any response.

But the building’s owner, Shaker Skaik, told us that the building was used as an observation point by Israeli forces during operations.

Israel said it bombed several compounds used by Palestinian snipers in the area in March.

Ground forces remained in Gaza City for several months during the first months of the war, and launched a second attack on Al-Shifa Hospital in March 2024, while Hadeel’s husband was receiving treatment inside.

With such a rapid population turnover, no one in the building now remembers what happened in those first months of the war.

But the fighting still continues around it.

Mona Shabt – Fifth floor

In the apartment above Hadeel’s house, Mona Amin Shabat, 59 years old, plays with her grandchildren under large bullet holes in the wall.

She explained: “Two days ago, bullets hit the inside of the building here.” “I grabbed the children and ran with them there, where it was safer. We sat there praying to God that it would be okay. The children were terrified.”

Mona is also from Al-Tuffah neighbourhood. She has lived here since August with her husband, three children and grandchildren. They don’t pay rent. Mona says that the family lost everything when their house was destroyed weeks after the war.

“They leveled the entire apple area to the ground, and not a single house remains,” she said. She told us: “We began life again, collecting spoon after spoon, plate after plate. Then famine came, and we ground up pigeon feed to eat, and lived on wild vegetables.” “After two years of war, I say that I am not alive, I am one of the dead.”

Another resident of the northern town of Beit Lahia told us that his area was now a “wasteland,” after the Israeli army razed it to the ground. “There are no more houses, or even any signposts, to tell you that there once was a neighborhood here,” he said.

The United Nations says that 90% of residential buildings in Gaza were damaged or destroyed. Entire neighborhoods, with their shared history, family ties, and social support, have been demolished.

But the idea of homeland is harder to destroy than bricks and mortar.

When the photographer visited Mona’s apartment, two of her granddaughters were drawing a picture. It is an idyllic, textbook image of a house – small and elegant, with a sloping red-tiled roof. The sun is floating on the horizon, the sky is pink and blue, and there are trees and plants.

It doesn’t look like where they live.

The widespread destruction of homes and communities often meant families were separated to survive.

Of Mona’s five children, two moved to the south, and another went to live with his wife’s family. Others came and went, she says. She and her husband even spent months apart from each other before moving to the Sukayk building, while Mona sheltered with her relatives.

The extended family that once surrounded her and anchored her world is vanishing.

“We are separated,” she said. “Separation is the hardest thing.” “My life has been taken from me. My health is gone. Our home is gone, and the people dearest to our hearts are gone, and we have nothing left.”

Shawkat Al Ansari – first floor

It is a feeling that Shawkat Al Ansari knows well.

Originally from Beit Lahia, now razed, he told us that his mother and sister were sleeping on the street in southern Gaza, while Shawkat lived with his wife and seven children on the first floor of the Al-Sikaik building.

Four months ago, his brother disappeared.

“He went to get flour from the house of one of our in-laws in Shujaiya [on the northern edge of Gaza City]. We still don’t know what happened to him. We looked everywhere but couldn’t find him.”

The constant movement of people on the move in search of food, safety or shelter made it difficult to keep families together.

“We were living well before,” Shawkat said. “Now my brother is missing, and we are all stranded in different places.”

One by one, the foundations that hold people in place – the home, the community, the family – have disintegrated due to the ongoing displacement of Gaza’s population and the destruction of its neighborhoods and streets.

Now, Shawkat sits in the empty concrete rooms of the Al-Sukayk building, watching the future slip away. He says that his children did well in school before the war, but now they forget how to read and count.

Constant movement freezes their lives.

A few days later, we received a call from Hadeel. She and several other families in the Skaik building were moving again.

She told us that Israeli forces threw smoke bombs around the area to indicate that they were about to enter.

“We didn’t see the tanks last night, but if we don’t leave now, we will wake up to them tomorrow,” she said.

Hadeel was packing when we spoke, planning to join her brother nearby before trying to head south together.

“We will stay on the streets and live in a tent,” she said. “No matter what we do, nothing will bring back what’s inside us. My children are no longer my children. There is more suffering than innocence in their eyes now.”

Across Gaza, the buildings that remained standing became transit centers for families brought together and separated by the war.

If negotiations succeed, peace may end their journey, and reconstruction may bring them a different kind of future.

But their old life is behind them.

This war has erased the path to the past.

Additional reporting by Amer Pirzada and his colleagues in Gaza. Designed by the BBC Visual Journalism team.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/34ee/live/88e540b0-a450-11f0-92db-77261a15b9d2.jpg

إرسال التعليق