Patronato: My mum was a 17-year-old free spirit in Franco’s Spain

2025-11-16 00:29:01

Linda Presley and

esperanza Escribano,Barcelona

BBC

BBCMarina Freixa always knew there was something dark and unspoken about her family.

Her mother grew up under the decades-long Spanish dictatorship, which ended in 1975, but details of her childhood are murky.

Then everything changed one Christmas a decade ago – when Marina was 20 years old.

On that winter evening around the table, with a cloud of cigarette smoke hanging in the air and empty wine glasses, Marina’s mother, Mariona Rocca Torte, began to speak.

Else Bates (documentary)

Else Bates (documentary)“My parents reported me to the authorities,” Mariona told them. “They put me in a reformatory when I was 17.”

Reformatories were institutions where girls and young women who refused to conform to the Catholic values of Franco’s regime—single mothers, girls with boyfriends, and lesbians—were detained. Girls who were sexually assaulted were imprisoned and held responsible for their assault. Orphans and abandoned girls may also find themselves living behind the convent walls.

Marina and her cousins were stunned.

They could not understand that their grandparents had arranged for their daughter to be imprisoned.

Mariona’s memory of telling this story to the young people in her family is blurred, she believes, as a result of the psychological “treatment” she was forced to undergo in the reformatory. But Marina did not forget the discoveries, and years later, she made a documentary telling her mother’s story.

Mariona is a survivor of the Patronato de Protección a la Mujer – Women’s Protection Council. Under dictator Francisco Franco, it oversaw a national network of residential institutions run by religious organizations. There is no specific information about the number of institutions involved or the number of girls affected.

Thursday will mark 50 years since Franco’s death. Spain has since witnessed a women’s rights revolution – but survivors of the Patronato case are still waiting for answers and are now calling for an investigation.

Family charity

Family charityWarning: This article contains content that some readers may find disturbing

The eldest of nine siblings, Mariona describes her parents as right-wing and extreme Catholics. They were so conservative that they wouldn’t let Mariona wear pants.

But in 1968, when she turned sixteen, a new world was revealed.

Mariona taught the children during the day, and prepared for college in the evening classes. There, she says, she met people she had never met before: trade unionists, leftists, and anti-Franco activists. It was a year of global protests against tyranny and the Vietnam War, with mass demands for civil rights. The spirit of revolution was contagious.

Franco was in power for three decades. Political parties were banned, censorship was global, and young people wanted change. Mariona soon joined her new friends in “raids”: a few of them would block the street, throw Molotov cocktails, hand out leaflets, and when the police showed up, scatter in every direction.

On Labor Day 1969, one of Mariona’s friends was arrested during a demonstration in Barcelona. There was a risk that the detainee would give names to the police, so Mariona could not return home, in case they were looking for her. That night she stayed at the apartment of a fellow activist.

When she returned home the next day, Mariona was in big trouble. Her parents were angry, and began to exert more control over her life.

“For them, it was a scandal, a disgrace to the family,” she says. “After that, they wouldn’t let me out.”

By the end of that summer, Mariona decided to leave home, traveled to the island of Minorca to spend the holidays with some college friends, and left a letter for her parents.

They immediately informed the authorities that she was a runaway minor, and just as Mariona was about to board the boat back to Barcelona, she was arrested.

Scientific

ScientificHer parents met her at the port of Barcelona.

They didn’t take her home. Instead, they took her to a monastery. Mariona gets no explanation, she only remembers her parents’ anger.

A few days later, she flew to Madrid with her father. There, she was transferred directly to another monastery, part of the Patronato Order, affiliated with the Spanish Ministry of Justice.

She and the other detained women were classified and separated.

Mariona says she ended up on the first floor, reserved for “rebels, whom they consider to be fallen women.”

The Patronato had the power to detain any nonconformist woman under the age of 25. These were not criminals – they were females considered in need of “re-education.” But Mariona never learned the stories of the others she was held captive with.

“They wouldn’t let us talk,” she says. “It’s unbelievable.” “And you wonder how they managed it?”

Female detainees were only allowed to exchange simple greetings with each other – a form of control and a way to prevent “bad” girls from influencing others.

“What you couldn’t do was meet another girl,” Mariona says. “Because they will separate you, and send one of you to a different dorm, or even to another institution.”

She believes there were about 100 detainees in the monastery. They slept 20 people in a room, with a nun at one end, and the door closed. The daily routine was exhausting: prayer, mass, cleaning the monastery, then spending hours in the workshop making clothes for local retailers. While the girls were sewing, one of the nuns was reading out loud so no one would talk.

“There was indoctrination,” Mariona recalls. “To understand that you behaved very badly. Once you realized that, you have to ask for forgiveness and confess.”

Mariona never confessed.

Marina Freixa

Marina FreixaAfter about four months, she was allowed to return to her home in Barcelona for Christmas, but was not allowed to go out alone. Somehow – Mariona doesn’t remember how – she managed to escape, but her escape was short-lived. Within hours, she was transferred to a car with her father and uncle, and returned to Madrid.

“We returned to the monastery at dusk,” she recalls. “I refused to come in. They dragged me up the stairs and gave me a sedative to get me inside.”

Inside the convent, the other young women were warned not to talk to her – the rebellious girl who had the audacity to try to escape. She felt very lonely and eventually started refusing food.

Drastic weight loss landed her in a psychiatric clinic. There, she says, she underwent two sessions of electroconvulsive therapy, followed by what is called “insulin coma therapy.”

Mariona says she was injected with insulin to induce profound hypoglycemia, a coma-like state caused by low blood sugar. It was thought that this could reduce the symptoms of psychosis or schizophrenia, and in some way “reset” the patient’s brain.

It was a “treatment” that was discontinued in many countries for one simple reason: it could be fatal.

Mariona received her insulin injection in the morning. Later she will be brought out of the coma and forced to eat. Mentally, I started to shut down.

“Every day, I felt more dizzy,” she says. “I started saying things like: ‘I hurt my father.’”

“I went through this application and acceptance process.”

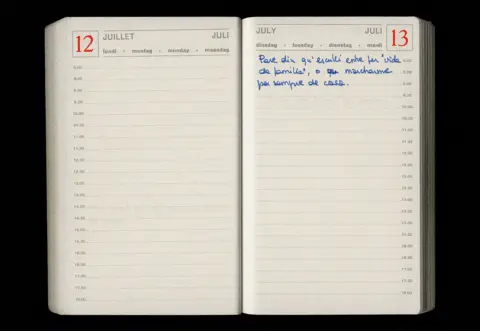

Mariona believes that forced “treatment” with intravenous insulin damaged her memory beyond repair. Suspecting that this made her forget things, she began keeping a diary. More than five decades later, this faded paper document from 1971 would tell Marina in the documentary about her mother’s experience.

Doctors thought the “treatment” would help Mariona gain weight, but that did not happen.

“One day, the psychiatrist decided it would be best to try tying me to the bed so I could eat.”

Mariona’s despair became unbearable, and she says she contemplated suicide. The psychiatrist then gave her a target weight of 40 kg (6 4 lb). If she achieved this, they promised to let her out of the clinic.

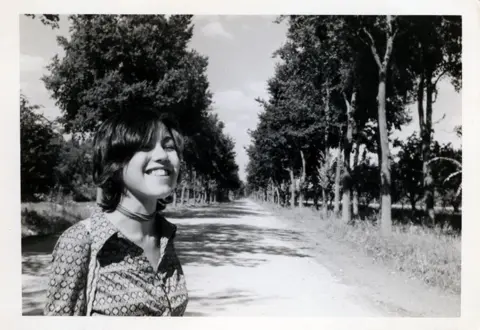

Mariona Roca Torte

Mariona Roca TorteMariona succeeded. In 1972, when she had become a little stronger, she returned to Barcelona.

Now 20, she has vowed never to live with her parents again.

These were the last years of Franco’s dictatorship before his death in 1975. Mariona moved from job to job, eventually starting her career as a television director. She had children, but her relationship with her parents remained cold.

At one point, Mariona asked her mother why she was being sent to the Patronato. Her mother only said: “We made a mistake.”

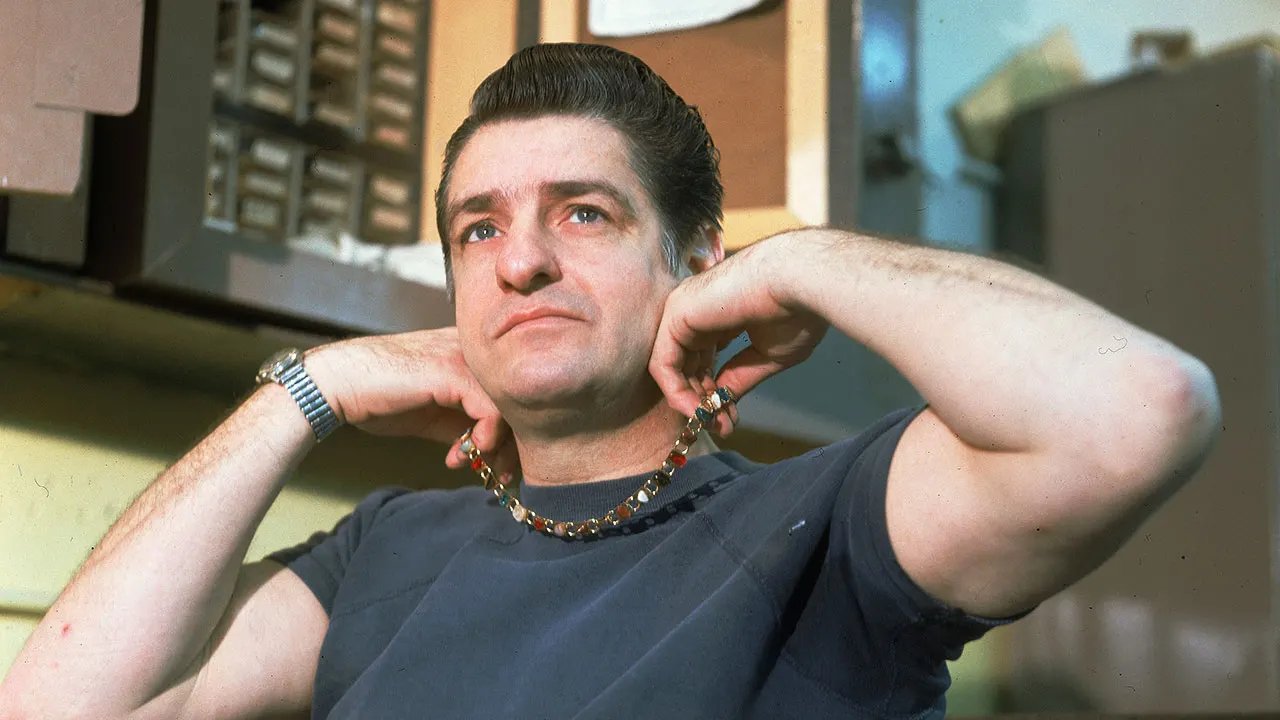

Mariona’s father is in his 90s now.

“We also suffered a lot,” he told her when she asked him about the family’s decision to imprison her in Madrid.

For Marina, learning more about her mother’s story complicated her relationship with her grandfather.

“I can’t force myself to love someone who has caused me so much pain – and who treated my mother so badly.”

The short documentary Marina made about her mother’s experience with Patronato is called Els Buits – Catalan for “spaces” – in reference to the blanks in Mariona’s memory. The film won awards in Spain, and was nominated for the prestigious Goya Award.

Esperanza Escribano

Esperanza EscribanoFifty years after Franco’s death, the film contributed to a groundswell of calls for women detained under the law to be formally recognized as victims of the Spanish dictatorship. Spain’s Minister of Democratic Memory, Angel Victor Torres, said his government was open to looking into the case of Patronato survivors.

Meanwhile, Marina and Mariona are touring with the film, taking it to community screenings.

“Women come forward and tell their stories – it’s like the door is open to something unknown, and that’s very powerful,” says Marina. “People think that what happened in their homes was an isolated incident. We try to say: This history is not individual, it was systemic.”

Her mother, Mariona, still doubts her memory sometimes.

But, she says, “seeing all of that reflected in the film gives it the weight of truth.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/57a8/live/3a7adaf0-c180-11f0-ae46-bd64331f0fd4.jpg

إرسال التعليق