When democracy was put on pause in India

2025-06-24 20:38:46

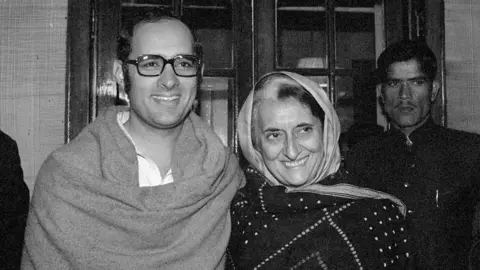

United Argument via Getty Images

United Argument via Getty ImagesIn the middle of the night on June 25, 1975, India – a young democracy and the largest world – froze.

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi just declared a state of emergency in the country. Civil freedoms, opposition leaders were imprisoned, the press, and the constitution turned into an instrument of absolute executive authority. During the next 21 months, India was still technically democratic but was working like anything.

The trigger? The bomb ruling was found by the Supreme Court of God that Gandhi is guilty because of the misconduct and nullified its victory in the elections in 1971. In the face of political step and an emerging wave of protests in the streets led by veteran socialist leader Japrakas Narayan, Gandhi chose to declare a “internal emergency” under Article 352 of the Constitution, citing threats of national stability.

In his new book on Indira Gandhi, the historian Serenath Raghavan notes that the constitution allowed large -scale powers during the emergency. However, what followed was “strengthening the unprecedented and unprecedented executive force … has not been destroyed by judicial scrutiny.”

More than 110,000 people, including major opposition political figures such as Morarji Desai, Jyoti Basu and LK Advani. The ban on groups of right to the extremist left. Prisons were crowded and torture was routine.

The courts, which were stripped of independence, presented a few resistance. In the state of Uttar Pradesh, which imprisoned the largest number of detainees, no single detention order was canceled. “No citizen can transfer the courts to enforce their basic rights,” Raghavan writes.

During a controversial family planning campaign, an estimated 11 million Indian – many by coercion were sterilized. Although the state -run program is officially, it was widely believed that it was organized by Sanjay Gandhi, the son of the elected Endra Gandhi. Many believe that a second mysterious government, led by Sanjay, is practicing unreasonable force behind the scenes.

The poor were more difficult. The cash incentives of surgery were often equivalent to a month or more income. In one of the Delhi neighborhood, near the borders of the state of Uttar Pradesh – which was called “Colonia” (places that were enforced sterilization) – it was said that the women said they were made Payas (Widows) by the state as “our men no longer men.” The police in Uttar Pradesh alone recorded more than 240 violent incidents linked to the program.

In their book on Delhi under emergency, civil security activist John Dayal and journalist Ajwi Boss wrote that officials were under severe pressure to meet sterilization classes. The novice officers applied the matter without mercy – the contract workers were said, “No offer, no jobs, unless you get vazistans.”

Gety pictures

Gety picturesIn parallel with this, the huge urban “cleaning” demolished approximately 120,000 of the slums, which led to the displacement of about 700,000 people in Delhi alone, as part of the improvement campaign that critics described as social cleansing. These people were thrown into the new “resettlement colonies” away from their workplaces.

One of the worst episodes of demolishing the slums occurred at the TURKMAN gate in Delhi, which is the longest Muslim neighborhood, where the police released the demonstrators who resist the demolition, killing at least six and solving thousands.

The press was left overnight. On the eve of the emergency, the ability to press newspaper is cut in Delhi. By morning, censorship was the law.

When the Indian Express recently published its release 28 June – it was delayed due to the power outage – left an empty space as the opening should have been. The statesman followed its example, and printing empty columns to refer to censorship. Even National Herald, founded by the first Prime Minister in India and Abi Indira Gandhi Jawaher Nehru, the slogan of the heads quietly fell: “Freedom is in danger, defending it with all your strength.” Shankar’s Weekly, a sarcastic magazine known for its caricature, was completely closed.

In her book – Personal History in Emergency Cases – Journalist Coomi Kapoor reveals the extent of control of the media through detailed examples of blackout orders.

This ban included reporting or photographing the demolitions of poor neighborhoods in Delhi, conditions in the Al -Aqsa Security Prison, and developments in the opposition -governed countries such as Tamil Nadu. The family planning engine was tightly controlled – no “negative comments or opening articles” was allowed. Even stories that are trivial or embarrassing have been cleaned: there are no “exciting” reports on a notorious, notorious sector and did not want a mention of the Bollywood actress in which the theft was caught in London.

Kapoor also notes that Mark took over from the BBC, along with the Times journalists, Newsweek, Daily Telegraph, were granted 24 hours to leave India for refusing to sign the “Control Agreement”. (After years of emergency, when Gandhi returned to power, Tully presented her to the head of the BBC.

He pushed some judges back. Bombay and Upper Courts have warned that censorship cannot be used on “the public’s brain washing”. But this resistance drowned quickly.

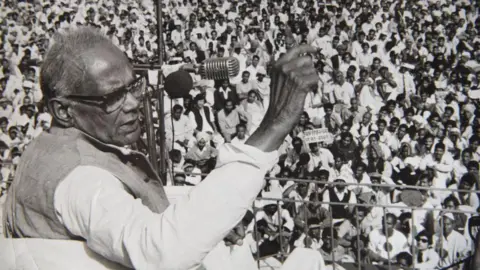

Keystone/Getty Images

Keystone/Getty ImagesThis was not all. In July 1976, Sanjay Gandhi prompted the conference for youth – the ruling conference party wing – to adopt its five -point personal program, including family organization, tree planting, dowry rejection, promoting adult literacy and the abolition of the class layer.

The President of the Congress DK Barooah instructed all local and local committees to implement the five Sanjay points, along with the official government program consisting of 20 points, which effectively integrates state policy with the Sanjay personal campaign.

The anthropologist Emma Tarlo, a rich ethnographic author of this period, wrote that during the state of emergency, the poor were “forced options”. It was also a turning point for industrial relations.

In their book, Christophe Gavrillot and Bratinaf Anil wrote in their book in the period they call the “first India dictatorship” of India’s dictatorship that the last remains of the working class policy have been supplemented. About 2000 labor union leaders were imprisoned, strikes were banned and workers’ advantages were reduced.

The number of human days lost to stopping – from 33.6 million in 1974 to only 2.8 million in 1976. The attackers fell from 2.7 million to half a million. The government also reduced its grip on the private sector, which helped the economy recover after years of recession. JRD Tata praised the refreshing system’s refreshing system and directed towards the result. “

Despite its heavy, the emergency was seen by some as a period of order and efficiency. Enda Malhotra, a journalist, wrote that in “at least the first months, the emergency to India has regained a kind of calm that he did not know for years.”

The trains ran on time, strikes disappeared, production increased, the crime decreased, and prices decreased after the seasonal winds of 1975 – which led to the stability that affects the need. “One of the facts is conclusive evidence of the reinforcement of the middle class – that any officials have almost resigned in protest against the emergency,” says historian Ramashandra Jeha in his book India after Gandhi.

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Images

Sondeep Shankar/Getty ImagesScientists believe that the harshest measures in emergency situations were largely confined to northern India because the southern states have stronger regional parties and more flexible civil societies that limit central exception. The Congress in Gandhi, who ruled federalism, had weaker control in the south, giving regional leaders greater independence to the resistance or moderate Draconian policies.

The emergency officially ended in March 1977 after Gandhi called the elections – and lost. The new Jatata government – a parties ’coalition of parties – fell many laws that it has approved. But deeper damage was done. As many historians wrote, the state of emergency revealed the ease of the democratic structures of the interior – even legally.

Historian Jayan Prakash wrote in his book in his book, “It is no wonder that the state of emergency is emotionally remembered in India … It seems that the Endera’s suspension of constitutional rights is a sudden coordination of the liberal democratic spirit that moved Nehru and other national leaders who established India as a constitutional republic in 1950.”

Today, the state of emergency in India is remembered as a brief authoritarian separation- deviation. But this framework, Brakash warns, generates “arrogant confidence in the present.”

“We have told us that the past has already ended, it has ended, it is a history. The present is free of its burdens. Indian democracy, we were told, was heroically recovered from the brief and brief adventure of Indira without any permanent harm and without any permanent problems, unannounced in its work,” Brakash wrote.

“It is a poor concept of democracy, which is considered only in terms of forms and procedures.”

In other words, this perception ignores the fragility of democracy when institutions fail to calculate power.

The emergency was also a flagrant warning against the risks of the hero’s worship – something embodied in the high political personality of Indira Gandhi.

In 1949, Br Ambedkar, the engineer of the constitution, warned the Indians against handing their freedoms to a “great leader”.

He said that the (dedication) was acceptable in religion – but in politics, it was “a certain path of deterioration and dictatorship in the end.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/8575/live/fb4e3ad0-4500-11f0-b6e6-4ddb91039da1.jpg

Post Comment